Getting Started with Luigi-TD¶

This tutorial will walk you through installing and configuring Luigi-TD, as well how to use it to write your first data pipiline.

This tutorial assumes you are familiar with Python and that you have registered for a Treasure Data account. You’ll need retrieve your API key from the web-based console.

Installation¶

You can use pip to install the latest released version of Luigi-TD:

$ pip install luigi-td

If you are using requirements.txt, put the following line:

# requirements.txt

luigi-td>=0.6.0,<0.7.0

Warning

<0.7.0 is necessary. Luigi-TD currently does not guarantee backward compatibility and can make incompatible changes in future versions.

Configuration¶

You can set your API key as an environment variable TD_API_KEY:

$ export TD_API_KEY=1/1c410625...

Alternatively, you can use Luigi configuration file (./client.cfg or /etc/luigi/client.cfg):

# configuration for Luigi

[core]

error-email: you@example.com

# configuration for Luigi-TD

[td]

apikey: 1/1c410625...

endpoint: https://api.treasuredata.com

Running Queries¶

Note

All scripts in this tutorial are available online at https://github.com/treasure-data/luigi-td/blob/master/example/tutorial/tasks.py

Queries are defined as subclasses of Query:

import luigi

import luigi_td

class MyQuery(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

def query(self):

return "SELECT count(1) cnt FROM www_access"

if __name__ == '__main__':

luigi.run()

You can submit your query as a normal Python script as follows:

$ python tasks.py MyQuery --local-scheduler

DEBUG: Checking if MyQuery() is complete

/usr/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/luigi/task.py:433: UserWarning: Task MyQuery() without outputs has no custom complete() method

warnings.warn("Task %r without outputs has no custom complete() method" % self)

INFO: Scheduled MyQuery() (PENDING)

INFO: Done scheduling tasks

INFO: Running Worker with 1 processes

DEBUG: Asking scheduler for work...

DEBUG: Pending tasks: 1

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) running MyQuery()

INFO: MyQuery(): td.job.url: https://console.treasuredata.com/jobs/19958264

INFO: MyQuery(): td.job.result: job_id=19958264 status=success

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) done MyQuery()

As you see INFO messages “td.job.url” and “td.job.result” in the log, you can access to the query result by opening the URL with your favorite browser.

Getting Results¶

You will often retrieve query results within Python for further processing. A straightforward way of doing that is to overwrite the run method and call run_query:

class MyQueryRun(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

def query(self):

return "SELECT count(1) cnt FROM www_access"

def run(self):

result = self.run_query(self.query())

print '===================='

print "Job ID :", result.job_id

print "Result size:", result.size

print "Result :"

print "\t".join([c[0] for c in result.description])

print "----"

for row in result:

print "\t".join([str(c) for c in row])

print '===================='

In this case, you can start processing the result as soon as your query completed:

$ python tasks.py MyQueryRun --local-scheduler

...

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) running MyQueryRun()

INFO: MyQueryRun(): td.job.url: https://console.treasuredata.com/jobs/19958264

INFO: MyQueryRun(): td.job.result: job_id=19958264 status=success

====================

Job ID : 19958264

Result size: 24

Result :

cnt

----

5000

====================

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) done MyQueryResult()

In practice, however, you should store the result before processing it when you build a data pipeline with Luigi. As you are working with “big data”, running a query could take a long time and retrieving the query result might be considerably slow. It is always recommended that you create a local copy of your query result and work with it.

A best practice of writing a query is to define an output method explicitly, just like you do with other Luigi tasks. For example, you can use luigi.LocalTarget, combined with to_csv, to save the result to a local file:

class MyQuerySave(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

def query(self):

return "SELECT count(1) cnt FROM www_access"

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget('MyQuerySave.csv')

def run(self):

result = self.run_query(self.query())

with self.output().open('w') as f:

result.to_csv(f)

Building Pipelines¶

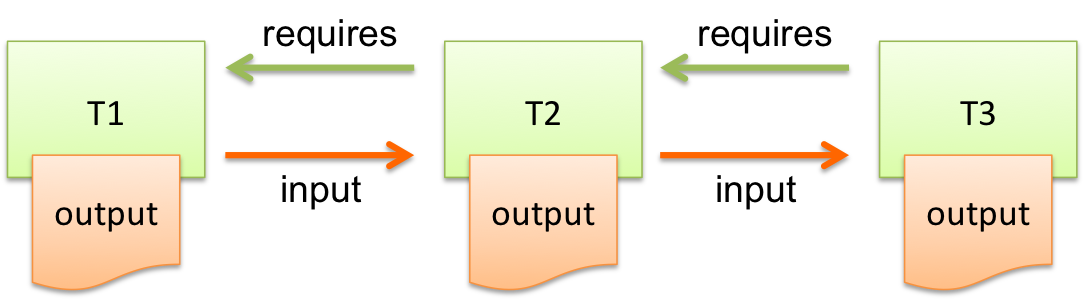

A “data pipeline” is a series of tasks, passing the result of one task to another:

Each task does substantial amount of work, and you want to run them step by step. For example, you can split your query into 3 steps:

- Running a query

- Retrieving the result

- Processing the result

Each output of a task works as a “checkpoint” in your data pipeline. You can restart your pipeline from the latest checkout when a task failed. Consider you had a bug in step 3 and you didn’t save the result in step 2. You would run the same query again and again until you fix the bug successfully.

Instead of retrieving the result immediately, you can use ResultTarget to save “the query state” to a local file:

class MyQueryStep1(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

def query(self):

return "SELECT count(1) cnt FROM www_access"

def output(self):

# the query state is stored as a local file

return luigi_td.ResultTarget('MyQueryStep1.job')

class MyQueryStep2(luigi.Task):

def requires(self):

return MyQueryStep1()

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget('MyQueryStep2.csv')

def run(self):

# retrieve the result and save it as a CSV file

with self.output().open('w') as f:

self.input().result.to_csv(f)

class MyQueryStep3(luigi.Task):

def requires(self):

return MyQueryStep2()

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget('MyQueryStep3.txt')

def run(self):

with self.input().open() as f:

# process the result here

print f.read()

with self.output().open('w') as f:

# crate the final output

f.write('done')

As you can see in this example, the preceding tasks are required by the following tasks, using requires methods. Luigi’s scheduler resolves the dependency and all tasks are executed just by running the last one:

$ python tasks.py MyQueryStep3 --local-scheduler

...

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) running MyQueryStep1()

INFO: MyQueryStep1(): td.job.url: https://console.treasuredata.com/jobs/19958264

INFO: MyQueryStep1(): td.job.result: job_id=19958264 status=success

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) done MyQueryStep1()

...

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) running MyQueryStep2()

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) done MyQueryStep2()

...

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) running MyQueryStep3()

cnt

5000

INFO: [pid 1234] Worker Worker(salt=123456789, host=...) done MyQueryStep3()

This looks complex at the first glance, but you will eventually find it being a natural way of building data pipilines. Every single task should define an explicit output method so you can avoid repeated execution of the same task.

Templating Queries¶

Luigi-TD uses Jinja2 as the default template engine. You can write your query in external files and use source to specify your query file:

class MyQueryFromTemplate(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

source = 'templates/query_with_status_code.sql'

# variables used in the template

status_code = 200

-- templates/query_with_status_code.sql

SELECT count(1) cnt

FROM www_access

WHERE code = {{ task.status_code }}

As you see in this example, a single variable task, which is an instance of your query, is available in the query templates. As a result, {{ task.status_code }} will be replaced by 200 at run time. You can define any variables or methods in your class and access to them through task.

If you prefer setting variables explicitly, use variables instead. In this case, you can access to the variables without task:

class MyQueryWithVariables(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

source = 'templates/query_with_variables.sql'

# define variables

variables = {

'status_code': 200,

}

# or use property for dynamic variables

# @property

# def variables(self):

# return {

# 'status_code': 200,

# }

-- templates/query_with_variables.sql

SELECT count(1) cnt

FROM www_access

WHERE code = {{ status_code }}

Passing Parameters¶

Luigi supports passing parameters as command line options or constructor arguments. This is convenient for building queries dynamically:

class MyQueryWithParameters(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

source = 'templates/query_with_time_range.sql'

# parameters

year = luigi.IntParameter()

-- templates/query_with_time_range.sql

SELECT

td_time_format(time, 'yyyy-MM') month,

count(1) cnt

FROM

nasdaq

WHERE

td_time_range(time, '{{ task.year }}-01-01', '{{ task.year + 1 }}-01-01')

GROUP BY

td_time_format(time, 'yyyy-MM')

In this example, the parameter year is defined as an integer. You can set the value by a command line option as follows:

$ python tasks.py MyQueryWithParameters --local-scheduler --year 2010

INFO: Scheduled MyQueryWithParameters(year=2010) (PENDING)

...

Your query template will be rendered using parameters, just in the same way as variables. You will get the following query, consequently:

-- templates/query_with_time_range.sql

SELECT

td_time_format(time, 'yyyy-MM') month,

count(1) cnt

FROM

nasdaq

WHERE

td_time_range(time, '2010-01-01', '2011-01-01')

GROUP BY

td_time_format(time, 'yyyy-MM')

Parameters are also useful to create unique names in output. Without unique names, Luigi will skip running tasks when the output already exists. If you are running the same query with different parameters, you should create different output names for all query submissions:

class MyQueryWithParameters(luigi_td.Query):

type = 'presto'

database = 'sample_datasets'

source = 'templates/query_with_time_range.sql'

# parameters

year = luigi.IntParameter()

def output(self):

# create a unique name for this output using parameters

return luigi_td.ResultTarget('MyQueryWithParameters-{0}.job'.format(self.year))

Congratulations! You are now ready to automate the process of running multiple queries with different parameters. You can set up cron for scheduled execution of your tasks, or write an aggregation task that requers your parameterized tasks:

class MyQueryAggregator(luigi.Task):

def requires(self):

# create a list of tasks with different parameters

return [

MyQueryWithParameters(2010),

MyQueryWithParameters(2011),

MyQueryWithParameters(2012),

MyQueryWithParameters(2013),

]

def output(self):

return luigi.LocalTarget('MyQueryAggretator.txt')

def run(self):

with self.output().open('w') as f:

# repeat for each ResultTarget

for target in self.input():

# output results into a single file

for row in target.result:

f.write(str(row) + "\n")